Over the course of three consecutive Saturdays in July 2010, the British artist, curator and writer Ian White (1971-2013) presented a trilogy of solo performances at the daadgalerie in Berlin. On the final night the audience were presented with a second staging of Democracy, a work first performed at Grand Arts, Kansas City the year before. We can watch a video of this performance now:

We join the back of a crowded, white-washed room, the camera’s lofty position giving us a clear view over the heads of those gathered a decade ago. We have arrived just in time: within a few seconds the artist rises against the opposite wall and waits for silence to slowly descend. Beneath the dying chatter, the BBC World Service plays and then a PowerPoint begins, the images of Elizabethan doublets and gardens blown out beyond recognition on our screens. After a while, White removes his jeans and makes his way with a slow, balletic step to the gallery exit, the free leg of his trousers trailing behind him. The camera turns to follow, but the view of him in the doorway is soon occluded by the bodies of other viewers watching as the artist vanishes into the city. Back in the room the audience breaks into applause. Some drift away; others mill around, chatting and watching the slide show, holding the space that White has just left.

Although we come now to his work after the artist has departed, we can still enter into that space and converse with those he has left behind. Across his almost two decades of writing, curating, performing and teaching, White’s capacious and wilful practice touched many colleagues and collaborators. From early programming positions at the Horse Hospital and the Lux Centre (later LUX) in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, White began to develop an artistic practice of his own. Between 2000 and 2013, he produced at least half a dozen solo performances alongside a number of collaborations with the artists Jimmy Robert, Every Ocean Hughes and Emma Hedditch.

Just as he resisted the tradition of the lone artist, White also denied the neat separation of his various activities. Each facet of his professional career was entangled with every other: they were ‘indivisible’ within a body of work that defies easy categorisation.1 Whilst the focus here is on White’s performances, we should be wary of drawing too clean a line around this genre. Many of these works give life to understandings gleaned through curatorial attention to the spaces and propositions of artist’s moving image, occasionally acting like a hybrid form of film programming themselves. By the same token, White’s performances are also textual, delighting in wordplay and engaging a fluid, writerly shape: ideas and phrases reappear in altered forms like an anagram, feeding White’s essays and blog posts which indulge in their own performative embodiment.2

Instead of being bound by disciplinary demarcations, White sought to turn them inside out and around, connecting them into a flexible rope that loosely borders his shifting output. Taking my lead from Democracy, with its hard, formalist poses receding towards smudged edges, I want to describe White’s performative practice as a similarly open form, concerned with manifesting the fluctuating conditions for production and reception as and in the work itself. However, this fluid figure raises a paradox: how can a shape be both defined and amorphous? This was a puzzle that occupied White throughout his career, structuring his practice and its engagement with the institutions and encounters that produced it, but that it also exceeded in imagination and complexity.

The question, however, in writing this introduction to White’s work, is how to follow him in materialising conditions here and now, on this (web)page? How to draw an outline of a practice that existed only in passing – or, looking again to Democracy, as a kind of passing through? Perhaps the answer can be found in some words from White himself. In a post on his blog Lives of Performers, the artist reflects briefly:

Which is to say that there might be something to be said for something I’ve started already to say more often… the thought that snares me, that

LIMIT IS MATERIAL.3

This phrase, here in bold and occupying a line of its own, trips the reader up, recurring as we explore White’s practice. It proposes a way to make the artist stay, to briefly hold him in the room. From the eternal present of Democracy, then, this essay will wind back to two of White’s earlier works before rushing forwards to the artist’s final two performances – making sense of his practice through its edges in time and in space. This will be a discontinuous outline to a discontinuous practice; a series of discrete descriptions of various works, ‘no more solid than a cluster of fault lines’ that, from a particular perspective, align into some semblance of form.4 This shimmering, between open and closed, unsettled potential and fixed edges, animates White’s practice: even when it has ended – reached its final limit – the work might still be going on, here and now, in the room we’re in.

Act One: ‘Not Ibiza, but the room we are in’

We begin with arguably White’s first solo work following his return to performing in the mid-2000s after a brief stint as the Cinema Curator at the Lux Centre. White once again took to the floor at the Horse Hospital where he had been the programmer and manager from 1995-2000, and which had been the site of his earliest performances.5 Although IBIZA: A Reading for ‘The Flicker’ was performed in 2008, it bears a striking resemblance to these formative works, consisting as they do of found or otherwise ambiguously authored texts read alongside audio and visual elements in a three-dimensional, embodied collage. White described his artistic practice as a process of ‘playing systems against each other’, with his role as ‘the vehicle […] rather than as the originating genius’: a concept that is refined in IBIZA where the artist appears as a kind of living frame.6

The frame is the first and most obvious limit of the artwork: the initial barrier we have to cross to reach its sacred enclave, sequestered away from the real world. As a performer, White is the physical boundary of his work: his frame and the frame collide. But in manifesting that gilt window within himself, the artist comes to stand both for that barrier and against it, producing an inviting and flexible edge that leaves the possibilities of the work open.

The performance notes for IBIZA describe the work in bald terms: ‘three ‘found’ texts are read and Tony Conrad’s film The Flicker is played at the same time as some of them’.7 A 16mm film comprised only of a title card and variously alternating black and white frames, The Flicker has a binary logic that, with the addition of himself as a third element, White spins into something more ambiguous. The conceit is that of no new creation: the work consisting only of a re-presentation of existing words and images, which come into contact through the presence of the artist himself. Throughout IBIZA, White sits at a small lamp-lit table with the audience in front of him and the film behind. The projection illuminates the back of his neck, the flickering of the film reflected on his skin. In the first performance at the Horse Hospital, White positions himself at forty-five degrees to both film and audience as he speaks. Directed towards nobody and nothing in particular, his words hang in the air between the seats and the screen, forming an invisible veil through which the audience comes to see The Flicker.

The preposition in the title is important: White reads for and not to. ‘For’ carries the sense of providing the necessary setting or circumstance for a thing to occur or become visible. ‘For’ frames an event, just as White frames the film, literally providing through his reading new ‘enunciative conditions of the art work’.8 The museum walls which usually hold the artwork fold inwards until White’s speaking body becomes the support, mediating the viewer’s interaction with the film. An artwork inside an artwork, a frame inside a frame.

But in (re)moving the frame from the gallery walls and projecting it onto his own body, White is not swapping one fixity for another. This frame is mobile, tensile and sensual: ‘any frame is a thrown voice’.9 White’s conception of the frame as a voice renders it formless: a practice not a thing. As a material reality, the frame provides order, separating inside and out, seen from unseen. White’s narration collides with and coheres to the spectacle behind him: a kind of verbal strobing to add to the visual. The performance begins with his reading aloud an email he sent to a friend about a weekend fling on the Spanish island of Ibiza. He describes smoking weed and having cold sex in his host’s immaculate modernist villa. The dazzling sun on the huge glass windows, the mind-altering effects of the drugs; these images fall alongside the hallucinogenic vibrations of Conrad’s film. Tales of homosexual encounters resound in the audience’s ears, re-coding the flickering film as queer itself: the flashing lights of a gay disco, the buzzed-out experience of chemsex.

Silhouetted in the strobing light, White is a disembodied yet very bodily presence, hovering between revealing himself and dissolving into the film. This fluid capacity is made sexual on the level of the text. After reciting his email, White reads his second and third found texts: adverts from gay cruising websites, before finishing with Yvonne Rainer’s No Manifesto. The final readings present a litany of erotic and then artistic exclusion: no to tops, to twinks and time wasters; no to spectacle, to style and seduction. A boundary is drawn and immediately transgressed as White announces his own affirmation in response to these firm negatives: ‘yes I do’.10 Invoking a kind of artistic and sexual consent instantiates the frame within the body of the performer or hook-up: an elastic line to be respected, removed or otherwise transgressed. White does not seek to force down this wall, but rather leans into it, enjoying the possibility of both its extension and retraction. The frame is revealed to be an open shape without essence: a vessel that can be inclusive and exclusive, turned inside out at the last minute to enclose something else.

Act Two: ‘No sense of an ending’

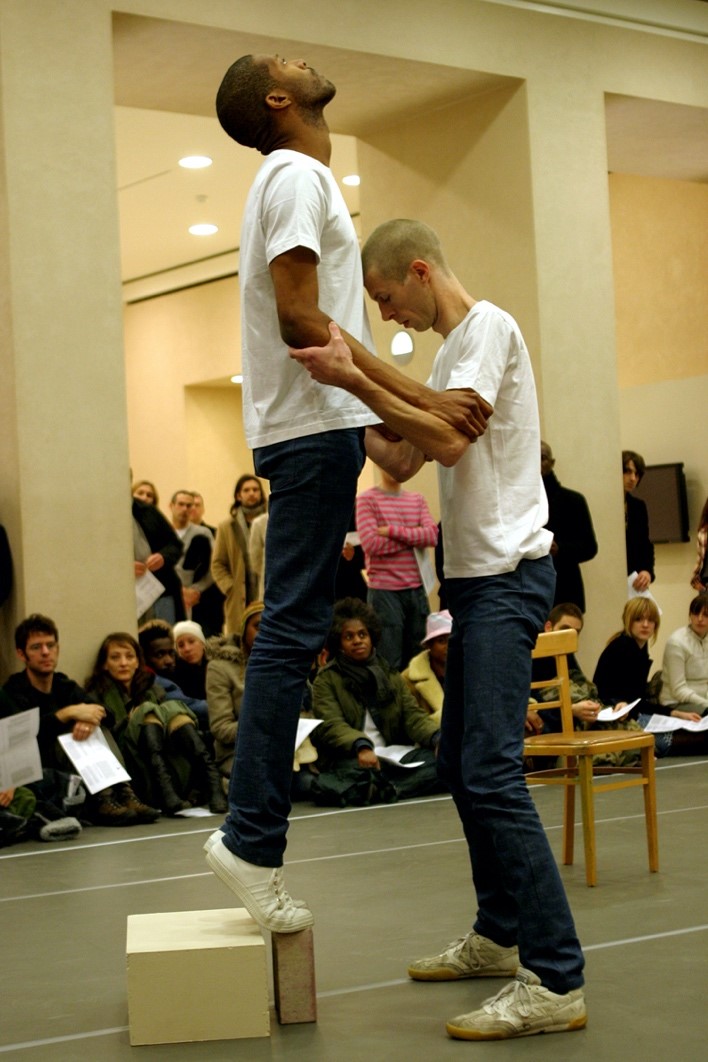

Yet the frame’s fluidity is in tension with its function: malleable as the border might be, it still bounds, still must leave its mark in order for White’s work to exist at all. There is still something to be pressed against: a line drawn and a decision made – even if they shift or move. The productive force exerted on and by these hard edges is apparent in 6 things we couldn’t do, but can do now, performed at the Tate Britain in 2004. This work was the first created in collaboration with the artist Jimmy Robert, who performs alongside White in a series of encounters which dramatize the transformative power of bodies working with and against each other.

Outside of 6 things, Robert had a similarly generative effect on White’s practice. Two years earlier the pair had, alongside the artist Emma Hedditch, staged a performative event together at Cubitt. ‘F. A. G.: Film, Art, Gainsborough’ was a significant moment for White: a new feeling of ‘making a work and saying, “I have authored this”’.11 The idea that an artwork might come into being through differentiation from a backdrop of other variously working bodies comes into a new focus in 6 things, where White and Robert’s moving forms rub alongside each other in a choreographed pastiche of everyday actions.

Robert described the piece as an attempt to build a ‘shared sense of limits’ with White through the undertaking of an arbitrary number of previously impossible tasks – mundane, workaday actions such as ‘play the piano’, ‘show a banner’, ‘hang a painting’ and ‘other things’.12 The whole performance revolves around a production of a particular embodiment in the presence of somebody (or something) else. Another person or a prop becomes a prosthetic that works with the performer to grow, bend, or otherwise (re)shape their body.

Early on in the performance, Robert attempts to balance on his tiptoes on two upturned breezeblocks. Unable to support himself alone on the narrow, wobbly bricks, he entreats White to help him. Arms braced, hands locked at each other’s elbows, the pair work mutually to produce a new physicality, expanding the limits of what Robert’s body could previously do. But this expansion is only temporary: as soon as White moves away, Robert must dismount. The pair remain fundamentally independent, separate in mind and body. 6 things is a ‘slow, and solitary confrontation with change: learning’ on one’s own what one can be alongside another.13

In Queer Phenomenology, Sara Ahmed suggests that queer bodies are produced by the hard edges of the world that frame and define them. Speaking of a passage in Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception where a doorframe appears in a crooked mirror, Ahmed describes how a body is forced to ““straight[en]” its view in order to extend into space’. By their very definition, queer people are precluded from this free expansion. Unable or unwilling to ‘straighten’ themselves, queer bodies and desires remain ‘twisted’, continually butting up against the jamb rather than sliding straight through.14

One can see this playing out in 6 things in Robert’s failed attempt to ‘straighten up’ on top of the bricks. Robert’s body pushes away from the breezeblocks and into White’s arms, his feet bending up, turning away from the hard surface. Ahmed makes us aware that ‘turning away’ is also a ‘turning toward’, or even a ‘turning into’: a spiralling motion in which turning away from limits is both its own kind of trap and a (limited) exploration of new possibilities.15 This corkscrewing movement is a central motif of 6 things. White and Robert rocket around the small taped-off square that is their makeshift stage, pacing its borders, crossing its diagonals: gestures of erratic circumspection that climax with the duo’s re-performance of Yvonne Rainer’s seminal 1966 dance piece Trio A.

Catherine Wood, then curator of performance at the Tate, with whom Robert and White developed 6 things, described the swelling fluidity of Trio A: ‘moving in so many different directions and configurations, the performer of the piece appears to be attempting […] to expand or maximise the potential for inhabiting the space available to him/her as fully as possible.16 The work magnifies the dancer’s physicality, encouraging them to take up space. In their marked-out rectangle White and Robert shrink and grow, swinging their hips, spinning like tops, scooping and slicing their arms and legs through the air: gangly and ungainly in white t-shirts and spray-on jeans.

Originally for three performers, Trio A’s final dancer is represented by Rainer herself via a bulky television monitor on which the film of her 1978 performance is shown. White and Robert perform the dance three times, each time rotating to face a different side of their box, turning Rainer’s monitor with them. With each revolution their movements get slacker, their timing more imprecise and out of step with each other as they tire. Like an anticyclone, White and Robert’s performance spirals outward, lengthening and loosening as it turns around on itself. At times it seems like either one might step outside of the taped border, but no sneakered foot ever crosses the line. In its use of Trio A as a readymade art object, 6 Things embodies the cramped position queer people occupy within the museum’s walls, having to perform disruption without overstepping the mark.

David Getsy has written about the conundrum queer bodies face in the art world’s institutional frames. Whilst artists use visual representation as a way to celebrate and bear witness to their existence, this strategy is in itself limiting, demanding ‘that difference be made visible, countable, and open to surveillance as a precondition for arguing that such identifiable divergence be treated like the norm.’17 6 Things is a direct intervention into the strategies of surveillance and documentation that exist in the museum. White and Robert were explicit about this work being an attempt to ‘mak[e] manifest [their] engagement with the museum, of positioning [themselves] within it and trying to understand the implications of that’.18

Their performance area was a perfect map of Tate Britain’s Art Now exhibition space traced onto the building’s Manton Street foyer and nineteenth-century gallery, where the first and second iterations of the work took place respectively. White and Robert force the Tate to perform its own existence within itself, making the institution visible material for comment.19 The pair’s real-like relationship is then introduced into this space to see what shape it would take there. 6 Things was the result of four years of friendship and six months of dedicated creative labour: a process that was, for White and Robert, ‘as much about coming to know each other as it was about finding a way of physically working together’. Despite the pair’s description of the performance as simply ‘spending some time with people as we have spent time with each other’ there is nothing neutral about the way their relationship is presented.20

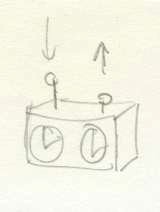

White and Robert perform the measuring and testing to which queer bodies are often subject in the museum and other public spaces. They stretch and lunge across their square, moving in diagonals like Olympic gymnasts. This sequence was apparently based on White’s ‘stalking’ of the gym instructor who worked across the road from him, and evidence of whose queerness White believed he had uncovered. Mimicking the instructor was an ‘elliptical response to the immensity of his blandness that had become an enigma’: White and Robert turn this abstraction in response to intense scrutiny away from him and onto themselves.21 Working out together appears as a linguistic and bodily rearticulation of the many months spent working together, crystallising this memory into a set of gestures that measure out these moments spent outside the gallery within its walls. White described how the performed tasks established ‘a mechanism to measure the time spent with others during the performance […] actions becoming a kind of clock’.22

Yet there is also a real clock keeping time throughout 6 things. The final act sees Robert carry off an old-fashioned dual-face desk clock that has been sitting at the front of their makeshift stage. These two ticking faces, which also feature in a preparatory drawing for the performance, call to mind some famous ancestors. Although it is unspoken, the resonance with Félix Gonzáles-Torres’s Untitled (Perfect Lovers) is unmistakeable. If one is to see White and Robert’s actions as ‘clocks’ then this final quotation unwinds the whole piece. Throughout 6 things the pair move constantly in and out of synch like the lovers’ battery powered hands. Dancing Trio A or lunging across the square, one will often lag behind the other before hastening to overtake. With their individual rhythms, White and Robert re-embody these clocks, bringing them back to the queer bodies to which they initially referred.

Getsy has observed how queer artists often turn to abstraction in order to evade the regulation that comes with visibility.23 Whilst Gonzáles-Torres abstracted himself and his partner Ross Laycock into manufactured objects in order to surreptitiously implant their relationship in the museum, White and Robert were faced with the different problem of how to avoid easy legibility whilst using their own bodies as material. By focusing on embodied practices rather than physical form, the pair could abstract their relationship beyond what is identifiable, producing instead a moving tableau of ambiguous encounters that slip beyond the museum’s walls. The clocks do not stop once the performance finishes, and neither do their hands start turning when it begins. For White and Robert, the piece has ‘no sense of an ending’, being ‘a continuous exchange’ that is only confined to the gallery for an instant.24

Ultimately, White’s sense of the frame offers an escape as much as a reaffirmation of the trap. In 6 things we see the paradox that faces him, and all queer artists, caught between necessity of fixed and legible form, and the feeling of it as an imposition that seeks to cramp and contain their experiences, twisting lives and trajectories until they are bruised from bumping against the walls that hold them back. Without these boundaries, however, the work cannot exist: indeed for White it only exists as a record of the marks left by the hard edge of convention, by the closing down of open possibilities just for the moment – keeping in mind the ticking clock until we can be let loose again.

Act Three: To ‘become live again’

The tension between the necessary limits that produce an artwork and his self-consciously slippery and unassimilable practice is one that White struggled (productively) with his whole career. His active engagement of this problem reached a crescendo in his final performances, Trauerspiel 1 and Trauerspiel Earthwork. The latter was given as a lecture at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague in 2012. Unlike IBIZA and 6 things, with their reframing of canonical pieces by other artists, this work cannibalised the earlier eponymous work, Trauerspiel 1, presented in Berlin just two weeks before. Instead of the original five dances and five 16mm films, the modified lecture contained ten still images of these sections accompanied by verbal descriptions and a live broadcast of the BBC World Service. In taking on his own performative history, White allowed himself a degree of license that he did not take with The Flicker or Trio A, which appear in his works as largely faithful renditions with minimal intervention. Trauerspiel Earthwork metabolises its previous incarnation, is thoroughly nourished and brought into being by this other work. Indeed, by re-presenting old elements in a new form, White wanted to ask ‘how something that was live could maybe become live again via becoming material of sorts’.25

Staging liveness here means materialising the temporal ‘ends’ of the piece: working in and out of the very moment of collapse. As though someone has pulled the plug from Trauerspiel 1, this second performance exists in a kind of suspended chaotic whirlpool. Trauerspiel Earthwork is plotted out by ‘three corners of a multi-dimensional triangle’ formed by the slideshow, White’s descriptions, and the radio.26 The elements cannot be tabulated but sit at odd angles to each other. Instead of running back and forth, up and down, information spirals downwards through this triangular funnel, images and sound mixing together in total confusion. In the lecture, the descriptions of the films are read over images of the dances, bleeding segments that had remained distinct in the stage performance into one another.

Trauerspiel Earthwork was presented as part of a symposium entitled ‘Rethinking Robert Smithson’, and one can think of White as enacting the artist’s famous metaphor of entropy: a ‘sand box divided in half with black sand on one side and white sand on the other’ run through by a child until ‘the sand gets mixed and begins to turn grey’.27 The sections that were so discrete in Trauerspiel 1 now blend like the differently coloured sand – White running back through his work and kicking it up, creating even more disorder. In a 2012 essay on the artist Ruth Buchanan, ‘What Is Material’, White did his own re-reading of Smithson’s sand box. Drawing attention to the reality of the metaphor, he reveals that this ‘analogy only holds for as long as we occupy a fixed position of inviolable, immaterial perspective’: from close up ‘the individual grains of sand in Smithson’s pit are not grey, but still black and white.’28 White notices and refuses the inertia implied by the now-mixed sand, the greyness that comes from staying still, in favour of constant motion as epitomised in Trauerspiel Earthwork’s ever-unstable collage.

White’s re-telling of this story has implications, like it did for Smithson, on his understanding of the art object and art historical time. The American artist sought to challenge the temporal commodification inherent in object-oriented art by arguing for the sedimentation of the artwork’s nature as such in every moment of its production, rather than a final stamp upon completion.29 Whilst White might agree with Smithson’s temporal logic of ‘breakdown’ rather than ‘breakthrough’, he resisted the closure of this process that was implied even by such elemental works as Smithson’s.30 Instead, the two Trauerspiels are indicative of White’s paradoxical attempt to arrest inertia by foreclosing any ending: by actively working against those temporal and spatial limits that ossify a work, introducing energy and motion – shifting the viewer’s perspective out of the grey.

Trauerspiel 1 was born out of White’s encounter with Walter Benjamin’s On The Origin of German Tragic Drama, and seeks to manifest on the stage his experience of reading and research, making the artwork’s production inseparable from its ‘final’ polished form. Part performance, part curated film programme, it is already an unwieldy chimera: its five dances and five films bridged by a sparse and poetic script that reads like provisional notes rather than a finished draft. At the right of the stage, as if to provide a visual metaphor for this continual work-in-progress, a naked man sits knitting throughout the entire hour-long run. Like the three fates of classical myth spinning the thread of life, he knots together his yarn, producing an accretive record of the time spent in the artwork’s play.

The artist described Trauerspiel 1 as an ‘allegory of Love and Time’.31 ‘What is Material’ defines allegory as an ‘empty form’ whose meaning is not just ‘contingent upon an act of interpretation’, but ‘its [very] material is contingency itself.’32 It appears then, that in these last works White finally found a form up to the task of holding the contradictions of his practice: the strict formalism and the flexible subjectivity, the rigid architecture of the auditorium and the open possibilities for relation it allows.

Act Four: ‘I can’t go on’

However, one of the problems with this kind of relational contingency is that it is dependent upon a connection that White can only hold (and therefore only be certain of) one half. The conceptual threads stitched together in Trauerspiel 1 might pass through the stage, but they originate and end up far beyond it. In manifesting its creation, White’s work leaks: messy conglomerations of process and affect spill over the spatial and temporal limits of the auditorium into the lives of those present. Yet the effect on the audience is unknown. The final words spoken in Trauerspiel 1 form an imperative: ‘Here is information. Mobilise desire’. An invitation of complicity is extended, but whether it is received, White cannot tell; he has no time to find out.

Invoking the spaces and emotions of (queer) desire is a continual strategy of White’s, so much so that we might use cruising as the phenomenon par excellence to describe the sociability his practice invokes. Like picking up a man in a park, everyone in the gallery is just going through the motions: making love is ‘a something done-to, put on, but a nothing touched. There’s the dumb thrill’.33 Whilst in sex (as in a performance), the two parties ‘become […] the same form precisely’ this connection is ultimately fleeting and we remain particles briefly rubbing against each other, like sand.34

White is constantly aware of the unsustainability of connection, both artistic and romantic. A post on White’s blog (Lives of Performers, begun in October 2012 following the artist’s diagnosis with lymphoma) entitled ‘His Name’s Not Bambi’ marks the final appearance of the titular junior doctor with whom he has been having an on-and-off flirtation during his treatment. Here, White’s narration reaches an impasse. He stumbles, he ‘can’t go on’, there are things that are ‘not OK to report’: ‘I’d be telling you about the private life of this person and it’s not mine, its walled-off from this’.35 White pushes up against Bambi’s walls but ultimately respects them at the cost of his own narrative, which trickles away. The ‘punctum snap[s]’, the story ‘leaks out, dribbles away, dries up’.36

Meaning, it seems, is reliant on relationships: the connection between people standing in for the links between moments that provide narrative sense. In Regent’s Park after his diagnosis White is stalked by a single magpie. It is a regular occurrence: ‘I could count the number of one’s [sic] I’ve seen as a string, a total within an allowance of intervals, a one plus one plus one etc., a cumulative line. Stupid.’37 The magpies refuse to be anything other than single, to flock into some narrative sense is beyond their bird brains, but White cannot shake the uneasy feeling caused by these illogical omens. In Lee Edelman’s analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds these winged creatures become arbitrary and unpredictable harbingers of anti-futurity, irrational grammarless agents of chaos punctuating the film’s narrative.38 White’s flesh-and-blood birds function similarly, organising themselves on the boating lake into a language he can’t understand. In their obscurity they are ‘something like thought’, by which White means that they are pure behaviour – a ‘simple action done simply’, a thing ‘stripped’, something so wholly exterior that there is no proof that ‘there is a thinking person INSIDE this body but precisely the opposite – that there is NOTHING INside, hidden, privileged.’39

This state of emptiness, of being ‘unaddressed, not bound by the empty game’ which is achieved by birds everywhere is found by White on stage.40 When he is performing, despite being the most basic condition of the work at hand, his presence is also strangely arbitrary: ‘I am here by chance’.41 The artist’s physical frame, its capabilities, its limitations – these are the only things that are important. Like birds, there is nothing inside; the audience perceives only the exterior of White’s body and connects his movement to the meaning of the artwork, rather than his interior state. In the end, this blankness is another way to say that what is material is the limit – the artist cannot get to the immaterial interior that hides behind each of our appearances in the auditorium.

Watching the aftermath of Democracy, we see what was once an artwork is now nothing more than a collection of bodies in a room (or pixels on a screen). There is always the potential of the space of performance being opened again; we can enjoy some facsimile of liveness much more easily than White’s efforts in Trauerspiel Earthwork. But for now, this marks an ending – of both the artwork and this essay – a somewhat fragmentary finale that befits both White’s practice and this piece of writing. Perhaps the only thing we can conclude for certain is that in this room (or on this page) ‘we all come and go’, producing our own shifting form from these fleeting interactions.42

1 Ian White, from unpublished notes for a talk entitled ‘Being Here’ at Ruskin School of Art, Oxford University in 2011.

2 The ‘anagram’ as formulated by Maya Deren was an influential concept for White, particularly in his teaching and film programming. See: Deren, M., An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film (New York, 1946); and White’s teaching notes for Experimental Film course, Middlesex University: Annandale-on-Hudson, Bard College Centre for Curatorial Studies, Ian White Papers MSS.022, Series IV, Box 3, Folder 96.

3 White, I., ‘F R E E (Prisons 2), Lives of Performers (October 29 2012), https://livesofperformers.wordpress.com/2012/10/29/f-r-e-e-prisons-2/ (23 November 2020)

4 White, I., ‘What is Material?’, in White, I., Sperlinger, M. (ed.), Here Is Information. Mobilise. (London, 2016), p. 281.

5 See the Works section of the website for details of one of his collaborative performances from his Horse Hospital period, Oedipus Rex, a concert symphony (with James Hollands, Ken Hollings & Andrew Walsh, 2000).

6 From unpublished notes to ‘Being Here’ talk.

7 White, I., Wood, C. (ed), Ibiza Black Flags Democracy (Berlin, 2010), p. 74.

8 Foster, H., The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge MA, 1996), p. 17.

9 White, ‘Statement for Appropriation and Dedication’, in Here Is Information. Mobilise., p. 291.

10 White, Wood (ed), Ibiza Black Flags Democracy, p. 77-9.

11 Bailey, G., Talker #1: Ian White (London, 2016), p. 12.

12 Annandale-on-Hudson, Bard College Centre for Curatorial Studies, Ian White Papers MSS.022, Series I, Box 1, Folder 16; Folder 15.

13 White, ‘Time/Form(s)/Friendship’, in Here Is Information. Mobilise., p. 244.

14 Ahmed, S., Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham NC, 2006), p. 66-7.

15 Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology, p. 77.

16 Wood, C., Yvonne Rainer: The Mind Is A Muscle (London, 2007), p. 91.

17 Getsy, D., ‘Appearing Differently: Abstraction’s Transgender and Queer Capacities’, in Erharter, C., Schwärzler, D., Sircar, R., Scheirl, H., Pink Labour on Golden Streets: Queer Art Practices (Berlin, 2005), p. 39.

18 Robert, J., White, I., ‘Jimmy Robert & Ian White: 6 Things We Couldn’t Do But Can Do Now’, in Wood, C, Keep On Onnin’: Contemporary Art at Tate Britain: Art Now 2004-7 (London, 2007), p. 37.

19 Annandale-on-Hudson, Bard College Centre for Curatorial Studies, Ian White Papers MSS.022, Series I, Box 1, Folder 15.

20 Robert, White, ‘Jimmy Robert & Ian White’, p. 37.

21 Annandale-on-Hudson, Bard College Centre for Curatorial Studies, Ian White Papers MSS.022, Series I, Box 1, Folder 15.

22 White, ‘Time/Form(s)/Friendship’, in Here Is Information. Mobilise., p. 244.

23 Getsy, ‘Appearing Differently’, p. 43.

24 Robert, White, ‘Jimmy Robert & Ian White’, p. 37.

25 White, Ian, Trauerspiel Earthwork, 2012, lecture with PowerPoint and radio, c. 20 minutes (documentation provided by the Estate of Ian White)

26 White, Trauerspiel Earthwork

27 Smithson quoted in White, ‘What is Material?’, in Here Is Information. Mobilise., p. 280.

28 Ibid., p. 280.

29 Roberts, J. L., Mirror-Travels: Robert Smithson and History (New Haven, 2004), p. 122.

30 Ibid., p. 125.

31 Annandale-on-Hudson, Bard College Centre for Curatorial Studies, Ian White Papers MSS.022, Series I, Box 2, Folder 32.

32 White, ‘What is Material?’, in Here Is Information. Mobilise., p. 280-1.

33 White, ‘(I am) For The Birds’, in Here Is Information. Mobilise., p. 334

34 Ibid., p. 334.

35 White, I., ‘His Name’s Not Bambi’, Lives of Performers (February 13 2013), https://livesofperformers.wordpress.com/2013/02/213/his-names-not-bambi/ (23 November 2020)

36 Ibid.

37 White, I., ‘1. What can be said’, Lives of Performers (October 7 2012), https://livesofperformers.wordpress.com/2012/10/07/what-can-be-sai/ (28 March 2020)

38 Edelman, No Future, p. 119-20.

39 White, I., ‘Thought & Behaviour (Matthew, Piano…), Lives of Performers (April 18 2013), https://livesofperformers.wordpress.com/2013/04/18/though-and-behaviour-matthew-piano/ (25 June 2020)

40 Ibid.

41 White, ‘(I am) For The Birds’, in Here Is Information. Mobilise., p. 333.

42 Ibid., p. 334.